Prehistory

The Prehistory exhibition of the National Museum contains some of Finland’s most significant archaeological findings. Spanning a period of 10,000 years, the exhibition features 700 objects that have been selected to shed light on the lives of ancient people. We selected a few of them for these pages – do they tell more about us?

Prehistory refers to the time before literacy. The scientific concept of the prehistoric era was developed in the early 19th century, when prehistory was divided into the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages according to the material used in weapons. Choosing and finding the materials needed for objects required a lot of knowledge and skill from prehistoric people. Stone was the first important raw material for tools and other objects. The use of stone as a raw material for objects was also continued after the discovery of metals. Bronze and iron were discovered in the Middle East, bronze in the 31st century BCE and iron around 1500 BCE. Metals enabled the development of entirely new types of objects, such as swords, knives and daggers.

Only some of the materials used have been preserved to our day. In addition to stone, clay and metals, objects were made using all materials found in nature, such as leather, fur, bone, wood, bark and hay. However, only a few of these have been preserved. In Finnish soil, organic matter is only preserved in oxygen-free conditions, such as in clay soil and bogs. This is why there is little information about clothing in the prehistoric era, for example.

Exhibits

Grave number 56 from Luistari, Eura

Sword from Pappilanmäki, Eura

Grave number 56 from Luistari, Eura

The cemetery of Luistari, Eura, was found in 1969 in connection with sewerage work. Archaeological excavations were carried out on the site in 1969–1992. The cemetery had been used for almost 800 years, during which time more than 1,300 people were buried there. Of these, about 400 graves have been examined further. The oldest graves date back to the Vendel Period, circa 600–800 CE.

In the Iron Age, weapons, jewellery and other objects were sometimes buried with the deceased. It was believed that these would be needed in the afterlife. Plentiful burial offerings reflected the position of the deceased and their family in the community. Especially during the Viking Age (circa 800–1050 CE), a lot of jewellery and utility items were placed in graves. Many graves with fewer or no objects were also found in the Luistari cemetery. Some of these graves without objects date from a later period, when Christianity was already influencing the burial traditions.

The woman buried in grave number 56 in Luistari was named the “Eura Queen” by the director of the excavation, Pirkko-Liisa Lehtosalo-Hilander. The grave was found during the first summer of digging in 1969. The grave was at a depth of approx. 80 cm in a field, in an area dense with graves. It was quite large, approx. 250 x 110–120 cm. Pieces of a wooden platform had been preserved under the objects, which were covered by a layer of wood and birch bark. Several subsequent burials had been made on top of the grave.

In addition to the objects, some of the deceased’s jawbone and teeth had been preserved, along with some bones of the upper arm, forearm and fingers as well as a hip and the remains of her shin bones. Based on these, it was estimated that the woman had been about 165–170 cm tall and had been buried on her back with her arms bent over her waist. According to dental analysis, she had died around the age of 45. The tooth enamel shows developmental abnormalities suggesting a possible deficiency disease in childhood. According to an osteologist, the woman’s hip joint shows signs of osteoarthritis.

Over the decades, a lot of research has been conducted on the Luistari cemetery. The results and literature references are available on Luistari’s own website. The excavation reports are available on the Finnish Heritage Agency’s website.

Digital collection

Sword from Pappilanmäki, Eura

Around 600–700 prehistoric swords have been found in Finland. The earliest swords are from the Bronze Age, but there is a particularly large number of known swords from the end of the Iron Age. Throughout its history, the sword has been the most prized of all weapons. Unlike spears or axes, the sword cannot be used for hunting or as a tool; it was developed for battle and harming another human being. An expensive item, it has been a symbol of the wealth and social status of its owner. The sword is also associated with beliefs about supernatural powers and qualities, even personality.

One of Finland’s most famous Iron Age swords is the ring-sword found in Pappilanmäki, Eura in 1939, dating back to the 7th century. The sword was found in the early spring of 1939, when a place for the boiler room was being excavated for the main building of the farm. The builders reported the discovery, and the sword was deposited in the National Museum’s collection on 29 March 1939 under the number KM11002:5. The large notch that appears in the middle of the scabbard is from a workman’s shovel.

The Eura sword is from a grave that was destroyed during construction work before archaeologists were able to examine it. Most of the items of the grave were probably recovered, but the placement of items in the grave, for example, could not be investigated in more detail. In addition to the sword, the items in the grave included a seax and the bronze rails of its sheath, a fragment of the tip of a spear, a fragment of the blade of a knife, a Permian belt with bronze ornaments, 30 pieces of leather and 13 pieces of birch bark from the belt and its charms, a belt buckle, a horse bit and its mounts, tweezers and an ornamental ring pin.

An attempt has been made to deduce the sex of the buried person on the basis of the items in the grave, as the bones of the deceased have not survived in the acidic soil of Finland. In 1940, Helmer Salmo interpreted the grave as belonging to a cavalryman from the Vendel Period. Weapons have usually been understood as belonging to a man’s grave. According to interpretations, the Permian belts in Finland and Scandinavia have also been found in men’s graves. In their native region, however, these belts are found mainly in women’s graves.

In the Iron Age, cremation was a common way of burying the dead, but in the Eura region, the dead were buried without cremation as early as the 6th century. As a result, objects and parts of clothing in graves have also been preserved for examination. Based on the findings, it can be concluded that the current Eura region was a prosperous area towards the end of the Iron Age, with good connections in many directions. The Pappilanmäki ring-sword is a prestigious object that may have been given as a gift to the owner. We cannot know for certain, because the objects found in the graves and their remains only give us a glimpse into the society and life of the Iron Age.

Digital collection

Select an image for more information

Snake buckle

Elk’s Head of Huittinen

Bronze axes from Tapaninkylä

Wooden god

Brooch from Laitila

Spearhead from Kirkkomäki, Turku

Clay pot

Stone axe

Animal head dagger from Pyhäjoki

Cross pendant from Taskula

Wooden elk head sculpture

Glass beads

Hansa dish

Bird scoop

Snake buckle

This bronze snake buckle was found in Hattelmala, Hämeenlinna, in 1925. The object was part of a hoard hidden at the base of a rock along with some other bronze jewellery and fragments. The items may have belonged to a bronze caster and/or been looted from cemeteries. The snake buckle has been dated to the Vendel Period around the 550–800s. Consisting of two intertwined snakes, the buckle is 8.1 cm long and 5.4 cm wide. The pin on the back has not been preserved, but the clips are still in place. Snake buckles of the same type have been found in many different variations and sizes.

KM8615:1

Digital collection

Elk’s Head of Huittinen

In the Stone Age, the elk was an important animal that was depicted in both rock art paintings and objects. Objects decorated with elks’ heads had a special significance for people of the Stone Age. One of the most famous animal head weapons found in Finland is the Elk’s Head of Huittinen, which dates back to the Mesolithic Stone Age.

The elk’s head was found in a Stone Age settlement in Palojoki, Huittinen. Based on the radiocarbon dating of a stove, the settlement dates back to approximately 6100 BCE (cal). The artfully carved object was probably modelled after a killed young elk about one year old. It is made of soapstone, which is soft and easy to work on, and has been carefully finished by grinding. The sculpture has a hole for fitting a handle, so it may possibly have been used as a staff or club. However, due to its soft stone material, the object was not suitable for use as a weapon or tool, so it was probably a valuable item.

KM6292:1

Digital collection

Bronze axes from Tapaninkylä

Two narrow-headed bronze axes were found in Tapaninkylä, Helsinki, in the 1840s. The axes are among the finest bronze objects in Finland. They are decorated with various line, dot and spiral patterns. This type of bronze axe is called a palstave. These axes are of the Danish type and date from approximately 1500–1300 BCE based on typology. Palstaves have flanges above the blade for attaching a wooden handle. Palstaves were made from bronze by casting into a mould and were suitable for both working and fighting.

The axes of Tapaninkylä were found as a pair near the Bronze Age shoreline. Bronze objects sacrificed in pairs in Scandinavia and Central Europe have been associated with the Bronze Age cult of divine twins, but it is very uncertain whether the axes of Tapaninkylä can also be associated with this same belief.

KM72:1a-b

Digital collection

Wooden god

This wooden sculpture of a human head was found during shore excavations in Pohjankuru, present-day Raasepori, in 1897. The object has been dated to the Neolithic Stone Age circa 4000–2000 BCE. The district engineer in charge of the excavation work donated the object to the Finnish Antiquarian Society. The object is narrow and flat, 24.5 cm high, 9.5 cm wide and 5.6 cm deep. The head has broken off under the shoulders. The transverse lines were created during the first conservation.

The object has been 3D modelled

KM 3481:1

Photo: Matti Kilponen

Digital collection

Brooch from Laitila

This silver brooch dating from the Viking Age was found in a field in Laitila in 1940. The person who found the large brooch thought it had come from a Russian plane during the war and put it on a fence pole. The brooch remained attached to the pole for a few months, until it was delivered to Turku and from there to the National Museum’s collections.

The brooch type probably originated in Ireland, from where it spread with the Vikings to Scotland, England and Scandinavia, and also to Finland. The Laitila brooch is the only brooch of this Irish type known in Finland. The brooch has also been called a thistle brooch due to its thistle-like spherical pins. The pins are hollow, flat on the back and decorated with ring patterns. There are also different patterns consisting of lines, triangles and dots along the brooch.

Brooches were used to fasten cloaks and other pieces of clothing. Large brooches were a visible indication of the owner’s wealth and position.

KM11243:1

Digital collection

Spearhead from Kirkkomäki, Turku

A large number of spearheads have been found in Iron Age settlements and graves in Finland and Sweden. Spears seem to have been very common in the era. Spears served as hunting and fighting weapons, and there were several different types of them. In the Viking Age (ca. 800–1050 CE), the spear also became a permanent part of the burial of arms. The iron spearhead was found in 1984 in Kirkkomäki, Turku, at the bottom of a grave during the excavation of the late Iron Age cemetery.

The spearhead from Kirkkomäki is of Petersen type G. The spearhead is a dagger-like, straight blade and slightly ridged. At the bottom of its shaft tube is a dragon pattern, which is a typical decorative motif in late Iron Age spears. By contrast, the small insect depicted at the top of the shaft tube, above the dragon pattern, is a more unusual decorative motif. There is still some of the wooden spear shaft left in the shaft tube.

KM22631:59

Digital collection

Clay pot

This clay pot has been dated to the Corded Ware culture circa 2800–2300 BCE. The pot is otherwise smooth, but it is decorated at the top with cord-like impressions typical of Corded Ware pottery. There is also a round radial pattern on the bottom. The largest diameter of the pot is approximately 11.9 cm and its height is 9.4 cm. There are thin cracks in its sides. The Corded Ware pot was found in Kårböle, Helsinki, in 1939. A local worker had found the object while driving sand from a sandpit and had brought it to the National Museum. The pot probably originates from a grave, of which there are several in the area at a depth of about half a metre.

The object has been 3D modelled.

KM 10981:1

Photo: Matti Kilponen

Digital collection

Stone axe

Dated to the Mesolithic Stone Age circa 8000–4000 BCE, this stone axe has a tapering rough base and a broad polished blade. The sides of the axe were made by striking on both sides. The object was found in a low ridge formation in the village of Turtola in Pello in May 1937. It was collected during an expedition by the North Ostrobothnian students’ association in 1938 and delivered to the National Museum in 1939. The object is 21.1 cm long, 8.5 cm wide and 3.7 cm thick.

The object has been 3D modelled.

KM 11032:1

Photo: Matti Kilponen

Digital collection

Animal head dagger from Pyhäjoki

Bear-head objects are connected to beliefs about the supernatural powers of bears. Since the Stone Age, the bear has been a powerful spirit animal alongside the elk. Objects depicting bears were valuables related to rituals and were not used in daily work.

This skilfully crafted dagger with a bear’s head handle was found in Pyhäjoki when extracting gravel right next to a Stone Age settlement. The object is made of light-striped Scandinavian (Köli) red slate. The end of the knife handle depicts a bear’s head seen from above, and the entire object has been carefully finished by grinding. There are no signs of use on the knife. This suggests that it was not an article of daily use.

KM13438:1

Digital collection

Cross pendant from Taskula

Cross pendants in Finland date back to the era of the crusades, from the 11th century onwards. They can be divided by type into crucifixes, palmette crosses and tri-circular crosses. The cross pendant found in a man’s grave in Taskula (Maaria), Turku, in 1938 is a crucifix. Crucifixes depict the image of the crucified Christ, and the opposite side of the pendant may depict either the crucified or some other image of a saint. The other side may also be blank. The crucifixes found in Finland are equal-armed and slightly wider at the ends of the arms.

The cross pendant of Taskula is made of silver and has the image of the crucified Christ on one side, and the other side probably depicts the Virgin Mary, whose wrists are tied to the arms of the cross. At the ends of the pendant’s braided chain are delicate, animal head-shaped end tubes. Exceptionally, there is a small cross on the head of Christ. The influence of the Eastern Church has been seen in the treatment of the subject.

The subject of the cross pendant strongly refers to Christianity, but it is nevertheless unclear what its significance was for its wearer. It is possible that the pendant did not reflect the wearer’s religious conviction, but was regarded only as a precious necklace, used regardless of the symbolism associated with it.

KM11275:29

Digital collection

Wooden elk head sculpture

This wooden elk head was found in a bog in Lehtojärvi, Rovaniemi, when digging a ditch in 1955. Based on the joints carved into the elk’s head, the object was probably a boat figurehead. Elk head boats were also depicted in rock art. However, the wooden elk head found in Lehtojärvi is the only evidence of the possible existence of such boats. The elk head was painted with red ochre, which also connects it with rock paintings. The object has been dated to about 8,000 years old and made in the Mesolithic Stone Age circa 6000 BCE. The elk head weighs 748 g and is approximately 37 cm long.

The object has been 3D modelled.

KM 14189:1Photo: Matti Kilponen

Digital collection

Glass beads

These colourful glass beads were found inside a brass bowl in Gulldynt, Vöyri, near the village of Bertsby in 1849. In addition to the beads, the bowl also contained bronze and silver jewellery and other metal objects. The dish broke when it was discovered. In addition to the glass beads, the necklace includes shells, possibly bone beads and a white agate in the middle. The necklace has been dated to the Vendel Period in the 550–800s. The beads in the necklace are not in the original order. In addition to beads, fancy women’s outfits included various buckles that held up the clothes.

KM68:1i

Digital collection

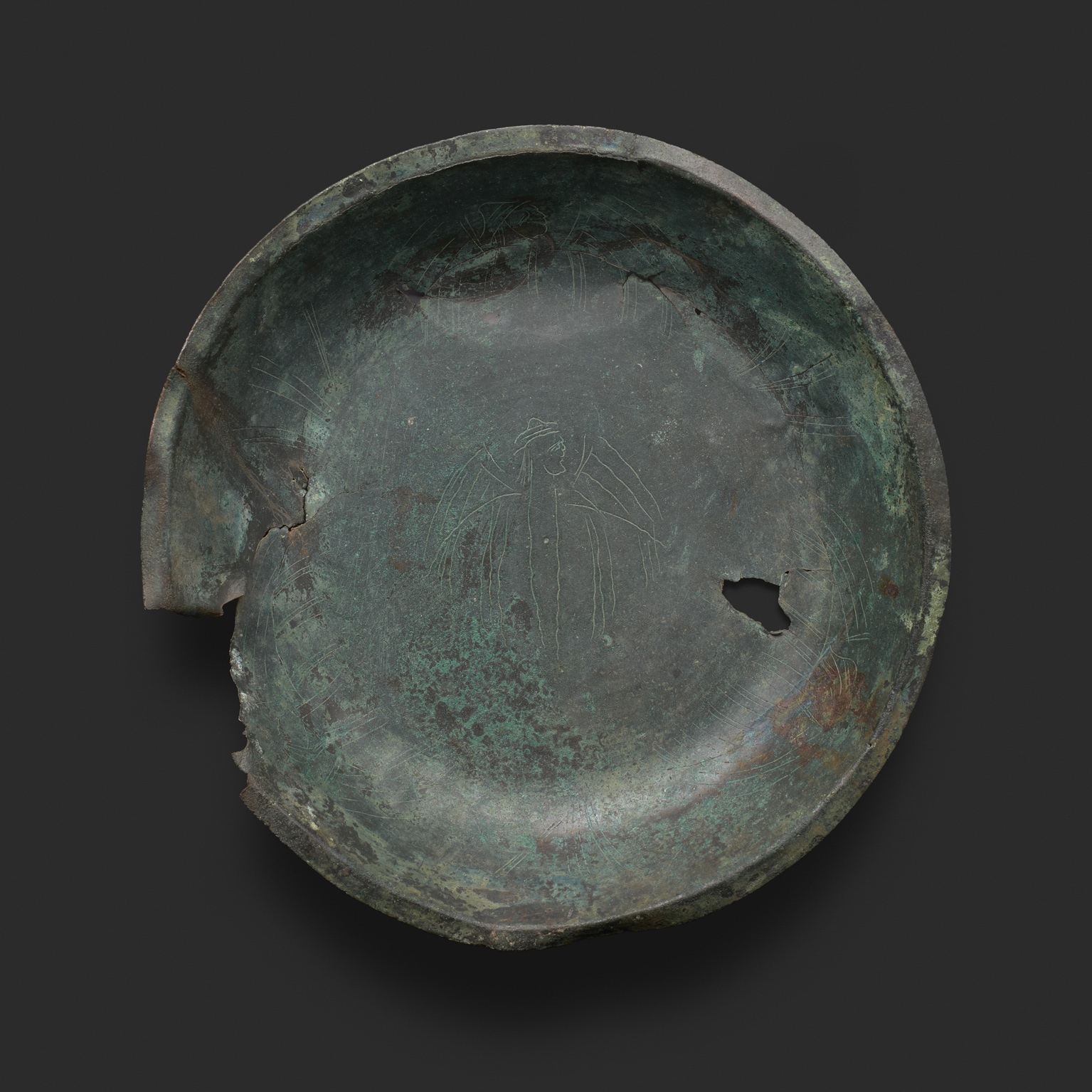

Hansa dish

This bronze Hansa dish was made around the 11th century. The surface of the dish features winged human figures at the bottom and sides, reflecting vices: idolatry, wrath, envy and arrogance in the middle. The dish was found in Kuhmoinen on the shore of Lake Päijänne in the early 1850s during cellar construction. The place was a burial site where human bones and other objects were found in addition to the dish, including a round buckle and the trim of a garment decorated with bronze spirals.

The dish is 25.7 cm in diameter.

The object has been 3D modelled.

KM 1232:1

Photo: Matti Kilponen

Digital collection

Bird scoop

A wooden scoop carved into the shape of a water bird. The object has been dated to the Neolithic Stone Age circa 4000–2000 BCE. Made of Siberian pine, the bird scoop is 13.25 cm long, 7.8 cm wide and 3.1 cm high. The scoop was found in 1914 in Vieki, Lieksa, south of the Savolanvaaranlampi pond, buried in mud at a depth of about 1.5 m. Objects made of Siberian pine were valuable imported goods, proving that people had extensive contact networks. Several animal-themed scoops have been found in the region of Finland; in addition to birds, the animals featured include bears and elk, which have been used as decoration motifs for handles.

KM 9003:1

The object has been 3D modelled.

Photo: Ilari Järvinen