Ruler received by Aleksis Kivi as a consolation gift

Artefact of the month – October 2023

Among the artefacts in Aleksis Kivi’s cottage, located at Seurasaari Open-Air Museum, is a ruler with bead embellishments. The records for this artefact state: Reportedly given to Aleksis Kivi by his “sweetheart”. Unfortunately, receiving the gift was not a joyous occasion for Aleksis Kivi. The ruler came as a consolation gift with a letter containing a refusal of an offer of marriage made by Aleksis.

Beautiful man without means

Aleksis Kivi was born on 10 October 1834 in the village of Palojoki in Nurmijärvi. His birth name was Alexis Stenvall, and this was the name he used throughout his life. Aleksis Kivi is his more commonly known pen name. The Stenvall family was poor, but the parents wanted to educate their gifted son. Aleksis Kivi’s father was parish tailor Eric Stenvall, the only literate person in the village of Palojoki. His mother Anna-Stiina (née Hamberg) was a seamstress.

However, Aleksis’ schooling was discontinued in the third grade in 1852 due to lack of funds. After that, he continued his studies privately and passed the matriculation examination at the age of 23 in the autumn of 1857.At that time, matriculation examination graduates usually came from families belonging to the gentry. In Nurmijärvi, Aleksis was the only one representing the common people.

The appearance of Aleksis Kivi is still a mystery. His portraits are based on a drawing made after his death. Ernst Forssell, a friend of Aleksis Kivi, drew Aleksis at the funeral, by his open coffin. Artist Albert Edelfelt, who never met Aleksis Kivi in person, made a more accurate drawing based on Ernst Forssell’s drawing, on which all subsequent paintings and sculptures are based.

Aleksis Kivi is said to have been a “somewhat beautiful man”; a tall, broad-shouldered man with a high forehead, beautiful hair and large brown eyes.

However, at the time of the proposal, Aleksis was a man without means. He had no income or profession, not even his matriculation examination certificate at that time. Aleksis sometimes walked around in “rags” and did not own many pieces of clothing. This may also have been the reason why he did not go to have his photograph taken.

Originally, Aleksis planned on becoming a priest. But after passing the matriculation examination, he decided to become a writer. As a priest, Aleksis would have had regular income and possibly a vicarage to live in. As a writer, he was subject to constant financial insecurity. Aleksis Kivi was the first writer to write in Finnish. There were few readers, let alone buyers of books.

Albina Palmqvist

The object of Aleksis Kivi’s affection and the giver of the ruler was the master tailor’s daughter Albina Maria Palmqvist (b. 1829 in Copenhagen). According to Viljo Tarkiainen, Albina was beautiful, refined and had small feet. Aleksis became acquainted with Albina’s family during his studies and he was a friend of Albina’s brother. Aleksis even lived with the Palmqvist family in their wooden house on Kaivokatu in the spring of 1853 for one semester.

Albina did not go to school, but she knew a lot about literature and encouraged Aleksis to read classics. In the Palmqvists’ home library, Aleksis got to explore the great names of world literature, such as Goethe, Schiller and Heine. Among the books were also Byron’s plays and all Shakespeare’s plays translated into Swedish. Aleksis was free to borrow the works he wanted, and Albina is also said to have given some of them to him. Most of the books were in Swedish and Albina did not know Finnish, so they socialised in Swedish. Albina and Aleksis used to discuss the books they had read. In addition to literature, the Palmqvists’ home was filled with music. Albina played the piano and her brother the violin.

Albina was five years older than Aleksis. At the time of the proposal, she was 25 years old and ready for marriage – girls in her social class used to be married off at a young age.

Impossible union

Aleksis Kivi’s proposal and hopes for a shared future with Albina were however impossible. Although both Aleksis and Albina were tailors’ children, there was a clear class division between them. Aleksis was the son of a modest village tailor, while Albina was the daughter of Albin Palmqvist, a wealthy master tailor. The difference in their social position was further increased by the fact that Albina’s paternal grandmother belonged to a noble family.

In the end, very little is known about the love life of the national writer. There is no solid evidence that Aleksis proposed to Albina, only recollections. There are different versions of the proposal itself. In the different versions, the proposal has been opposed by the father, mother and even Albina herself. In the romantic version, however, Albina is said to have had a crush on Aleksis and wanted him. There are even stories about a second proposal to Albina, but Aleksis was rejected again. It is no longer possible to find out the truth.

In Aleksis Kivi’s poem Kontiolan kaski (Swidden in Kontiola), there is a section where the father does not agree to the union of the two lovers:

But his forehead is obscured by despair,

Because without hope is the heart’s prayer,

As the lips of the maiden’s father did not utter

A word of hope, promise of a future together.

Aleksis Kivi used themes of his personal life in his literature, including negative ones.

Unmarried and sick

In the end, Albina did not marry at all. According to Viljo Tarkiainen, the main reason for Albina not getting married was her dread of marriage. Albina saw unions around her that did not fulfil her expectations of what marriage should be like. Albina’s own parents also quarrelled with each other, and Albina did not get along with them. Life in a quarrelsome family was painful. Albina is said to have been fragile and suffered from neurological issues.

She did not, however, end up alone. Albina’s brother Edmund died of a heart attack in 1871, after which Albina raised his 7-year-old daughter Anna. Three generations formed a shared household when Albina and Anna lived with Albina’s mother. Anna married Matti Kurikka from Ingria at a young age, but the marriage ended in divorce. Matti Kurikka was a well-known journalist, theosophical writer and head of the socialist community called Sointula in Canada. Albina died of pneumonia in Helsinki in 1903.

But her suitor did no better. The most devastating things in Aleksis Kivi’s life have been said to have been the constant lack of money and his relationship with women. His books sold poorly and Professor August Ahlqvist’s endless criticism was depressing.

Aleksis was unluckily in between social classes. He did not belong to the gentry, but neither was he one of the common folk. In Aleksis’ youth, it was rumoured that his grandfather was the illegitimate son of Carl Henrik Adlercreutz, chief judge of the district court, because the Adlercreutz family had supported the Stenvall family. These rumours were, however, proven unfounded a few years ago with the help of a DNA test. Young ladies in the countryside knew Aleksis as a ‘gentleman’ who owned only debts, manuscripts and dreams about writing.

Aleksis Kivi was attracted to many women during his life, but repeated rejections discouraged him, so he never married.

In the end, Charlotta Lönnqvist (1815–1891 Siuntio) became an important woman and benefactor in Aleksis’ life. Aleksis lived with Charlotta in Fanjunkars croft house in Siuntio in 1864–1871 and wrote, among other things, his main work Seitsemän veljestä (The Brothers Seven) there. However, the coexistence of this unmarried couple was not accepted, and there was much gossip in the village about the nature of their relationship. Charlotta was almost twenty years older than Aleksis. The nature of their relationship is still debated.

Aleksis Kivi suffered from various pains and physical weakness and contracted typhoid several times. In addition to these, he started to suffer from mental disorders that eventually led to his admission to Lapinlahti Mental Hospital. In Lapinlahti, Aleksis’ condition was diagnosed as chronic melancholia caused by anaemia, drunkenness and violations of his honour. As his condition was deemed to be incurable, Aleksis was transferred to live with his brother Albert in Tuusula. There he died at the age of 38 on New Year’s Eve in 1872.

Aleksis Kivi’s collection in Seurasaari

Aleksis Kivi’s cottage was purchased from Ms Hulda Karelius and placed in Seurasaari in 1913. However, the building burnt down during the erection work, so a cottage similar to the original one was built on the site. Fortunately, at the time of the fire, all artefacts intended to be placed inside the cottage were stored elsewhere and thus saved. Aleksis spent at least the summer and autumn of 1863 in the cottage and prepared his plays Kullervo and Nummisuutarit (Heath Cobblers) there. The artefacts belonged to Aleksis’ parents or to him.

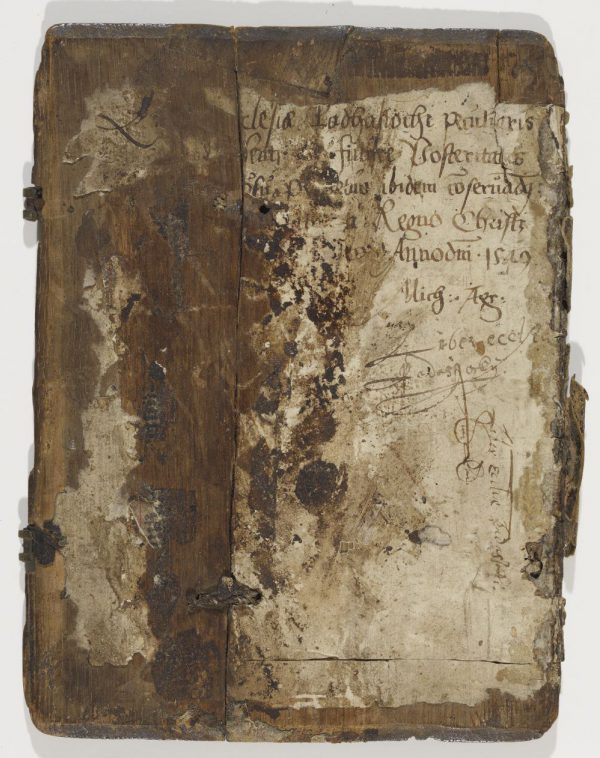

The ruler was obtained for the museum’s collections in 1915 through Arvid Grotenfelt, a professor of philosophy at the University of Helsinki. Aleksis Kivi’s brother, Juhani Stenvall, wrote to Arvid Grotenfelt in 1903 about Aleksis’ artefacts that he had in his possession and among them was the ruler. According to the brother, the ruler had been Aleksis’ cherished treasure: “… because he had received it from his sweetheart, in such a way that it was delivered to Aleksis by a maid of the same family along with a sealed letter containing a rejection to his proposal… The young lady’s parents were against their marriage.”

The ruler is made of wood and it has a perforated plate with embedded beads. One could assume that the ruler was intact when Aleksis received it. He must have used it a lot, as most of the beads have fallen off. The ruler is not intended for measuring, as it has no dimension markings. Presumably, Aleksis Kivi used it as a reading aid to follow the lines and underline things.

The day of Aleksis Kivi is celebrated on 10 October. It is also Finnish Literature Day.

Sari Tauriainen

Sources

Keskisarja Teemu, 2018. Saapasnahka-torni. Aleksis Kiven elämänkertomus. Siltala. Livonia print. Latvia. ISBN 978- 952-234-385-7.

Rahikainen Esko, 1998. Lumivalkea liina. Aleksis Kivi ja rakkaus. Like. ISBN 951-578-579-0.

Tarkiainen Viljo, 1984. Aleksis Kivi: Elämä ja teokset. WSOY.

Aleksis Kiven sukujuuret on nyt selvitetty varmuudella – sitkeät huhut Kiven aatelisjuurista eivät pidä paikkansa https://yle.fi/a/3-10768853

Aleksis Kivi, kansalliskirjailija https://www.nurmijarvi.fi/aleksis-kivi/elama-ja-persoona/

Kivi, Aleksis 1834–1872, Kansallisbiografia, henkilöhistoria. SKS https://kansallisbiografia.fi/kansallisbiografia/henkilo/2826

Lönnqvist, Charlotta 1815–1891, Kansallisbiografia, henkilöhistoria. SKS https://kansallisbiografia.fi/...

Sihvo Hannes. Miltä Aleksis Kivi näytti. Hiidenkivi nro 3/2000. https://archive.ph/20130429163542/http://www.aleksiskivi-kansalliskirjailija.fi/fi/index.php?Itemid=120&id=106&option=com_content&task=view

-

2024

-

2023

-

Book cover

Book cover

-

Pennies found in Häme Castle

Pennies found in Häme Castle

-

Ruler received by Aleksis Kivi as a consolation gift

Ruler received by Aleksis Kivi as a consolation gift

-

Caishen, god of wealth

Caishen, god of wealth

-

Sober curious phenomenon

Sober curious phenomenon

-

Summer shoes made of fish leather

Summer shoes made of fish leather

-

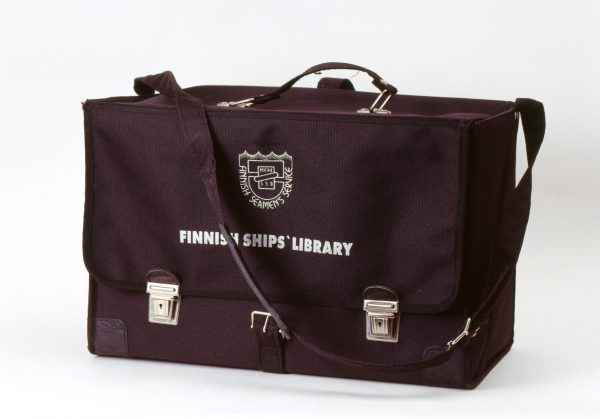

Book briefcase of the Finnish Seamen's Service

Book briefcase of the Finnish Seamen's Service

-

Nyytinkirukki lace pillow

Nyytinkirukki lace pillow

-

Arctic vessels and scale models

Arctic vessels and scale models

-

Portrait of a young dandy: Carl Gustaf Mannerheim

Portrait of a young dandy: Carl Gustaf Mannerheim

-

Painted Wall Covering in the Devil’s Chamber

Painted Wall Covering in the Devil’s Chamber

-

Šerkämä – Women’s brooch

Šerkämä – Women’s brooch

-

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

2019

-

2018