Painted Wall Covering in the Devil’s Chamber

Artefact of the month - February 2023

Amongst the remaining 17th–19th-century decorations at Louhisaari Manor in Askainen, the so-called Devil’s Chamber is probably the most well-known, particularly because of its painted 18th-century wall coverings. The most fascinating one of these paintings is the Baroque landscape of a garden on the back wall, while the name of the room itself comes from the face of a satyr on one of the pilasters. However, studying these wall paintings has proved difficult.

Even the way in which the wall paintings have been arranged at Louhisaari poses a problem. It arises from the fact that the probate inventory of a former owner of the manor, Carl Erik Mannerheim, from 1836 mention that there used to be two rooms where the Devil’s Chamber is now located. If the chamber was transformed into a single room later, the painted wall coverings could not have been there before that. On the one hand, the probate inventory mentions the names of two rooms that were in use in 1836, but on the other, there were not enough panels for two rooms. Furthermore, based on how high the ceiling and the wall coverings are, the panels could not have been on another floor either. Therefore, we can surmise that the paintings were brought to Louhisaari after 1836. This likely happened in the second half of the 19th century, because Carl Robert Mannerheim who inherited the manor in 1863 decorated Louhisaari with antiques with the aim of creating a historically rich whole.

The wall coverings in the Devil’s Chamber probably include paintings from two separate periods. When they were placed on the walls, they were also complemented by painting new panels as the number of the original paintings was insufficient to fill the entire room. On stylistic grounds, this may have taken place around the end of the 18th century, for example because the satyr’s head is surrounded by a grid pattern, typical to the late Gustavian style. But this brings us back to the question about the room’s structure, which is why we must assume that the complementary paintings in the Devil’s Chamber were not made unit the latter half of the 19th century.

The terminus post quem of the wallpapers in the Devil’s Chamber is 1748, because the decorations on a chest belonging to the shoemakers’ guild in Turku make use of the same park motif as the wall covering. We can assume that the model was an engraving, because guild painters often took advantage of European printmaking when creating decorations of this type. The image painted on the lid of the guild’s chest even has the same Rococo frame as the landscape in the Devil’s Chamber.

The Baroque garden pictured in the wall coverings is yet to be identified, but we can assume that the engraving that served as its model did represent a real existing garden in Europe. The previously proposed locations include Kungsträdgård in Stockholm and Drottningholm, but this may be because they were the closest Baroque gardens to Louhisaari.

Based on the style of clothing that the people in the landscape piece are wearing, the original engraving was probably made in the 1730s or 1740s. But because the artist of the engraving and the inspiration behind it are unknown, the only clue is that it was made before 1748. However, this alone does not help solve the puzzle. The only method that could be used to make the identification would be to go over as many engravings and illustrations of European gardens from the early 18th century as possible. That too has proved surprisingly difficult, even though these days the internet provides us with a significantly easier access to a large amount of artwork, thanks to libraries and museums that have opened up their collections online. Only a few engravings that depict similar-looking gardens have been found, but no exact matches. This matters because it is likely that the right engraving matches the landscape on the wall covering at a detailed level. Some variation is to be expected when it comes to the human figures, but the other elements of the garden and the architecture of the building in the background should match each other.

Based on an engraving, Nymphenburg in Munich, built by the Bavarian kings in the late 17th century and early 18th century, looked very similar. However, as no engravings that would match the wall covering have been found, we are unable to stick to this identification. But the engraving depicting Nymphenburg is a good example of how the trees and topiary around the edges of the garden have been misinterpreted in the painting in the Devil’s Chamber: the thin trunks did not grow from inside the hedges, but instead were probably in front of the bushes or, even more probably, behind them.

Another park that resembles the landscape in the Devil’s Chamber is Sorghvliet in The Hague. The park and the house within it were established by a Dutch councillor and poet Jacob Cats in 1643. As the name implies (‘Carefree’), the park was intended as a place for Cats to forget about the fuss and worries of urban life. No engraving of Sorghvliet that would perfectly match the painting on the Devil’s Chamber’s wall has been found, but Tonneel van nederlandse lusthoven, a picture book published by Jan van de Aveelen and Nicolaes Visscher in 1718–1748, illustrates Dutch castles and parks and contains an image of a park that ought to be compared to the Devil’s Chamber’s painting. The book was partially put together by using previously published images, and the engraving of Sorghvliet by Johannes Covens and Cornelis Mortier was made in the 1690’s.

In it, the park is depicted from the same perspective as the one in the Devil’s Chamber – using only a single vanishing point – but the eyelevel of the engraving is higher than that of the painting. The hedges and trees around the perimeter are dissimilar, and the image of Sorghvliet does not include the balustrade, gate or stairs nor the basin seen in the foreground of the wall painting. Although Covens and Mortier’s engraving of Sorghvliet is not a perfect resemblance of the wallpaper in the Devil’s Chamber, it is the closest match.

Therefore, until the exact match is found, we might call the theme of the scenery in the Devil’s Chamber carefree.

Jouni Kuurne

-

2024

-

2023

-

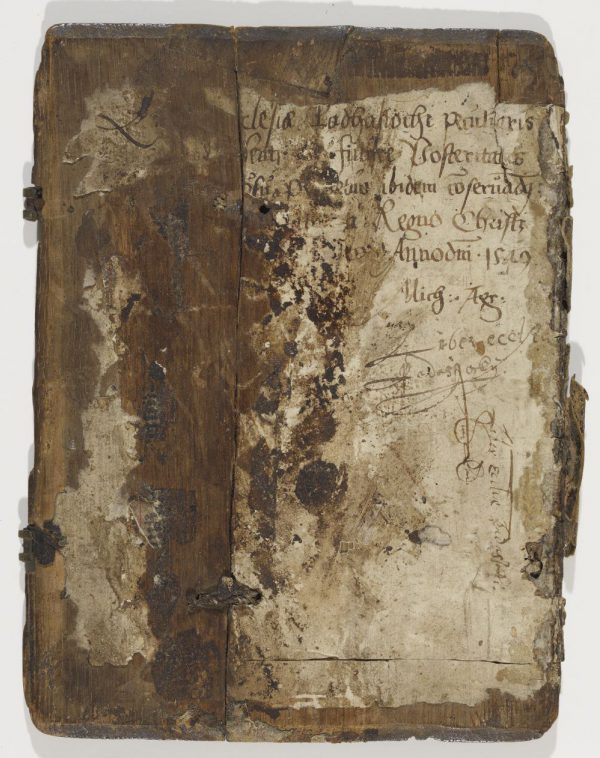

Book cover

Book cover

-

Pennies found in Häme Castle

Pennies found in Häme Castle

-

Ruler received by Aleksis Kivi as a consolation gift

Ruler received by Aleksis Kivi as a consolation gift

-

Caishen, god of wealth

Caishen, god of wealth

-

Sober curious phenomenon

Sober curious phenomenon

-

Summer shoes made of fish leather

Summer shoes made of fish leather

-

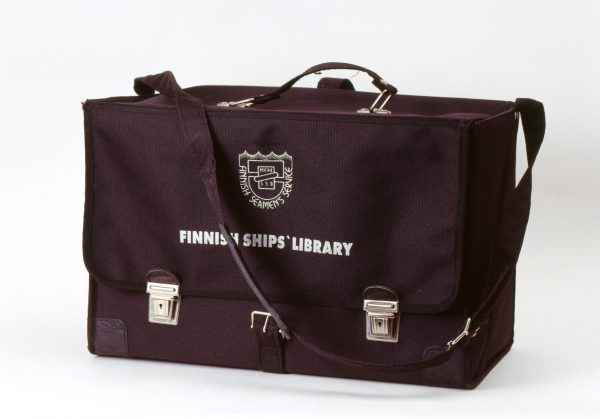

Book briefcase of the Finnish Seamen's Service

Book briefcase of the Finnish Seamen's Service

-

Nyytinkirukki lace pillow

Nyytinkirukki lace pillow

-

Arctic vessels and scale models

Arctic vessels and scale models

-

Portrait of a young dandy: Carl Gustaf Mannerheim

Portrait of a young dandy: Carl Gustaf Mannerheim

-

Painted Wall Covering in the Devil’s Chamber

Painted Wall Covering in the Devil’s Chamber

-

Šerkämä – Women’s brooch

Šerkämä – Women’s brooch

-

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

2019

-

2018