Retro upholstered baroque armchair

Artefact of the month - October 2019

The secondary upholstery of sitting furniture in museum collections is a mixed issue: for one thing, the upholstery is part of the history of the furniture and therefore of interest. Most of the time, however, it may be in a different style and thus, from a style-historical point of view, give a wrong picture of the appearance that is considered authentic or proper for the piece of furniture in question.

This baroque armchair was made circa 1710. The chair is an English-influenced high-backed model typical of the era. In addition to England, these chairs were also manufactured e.g. in Germany. The chair is made of walnut, and was probably imported into Finland. The seat and back of the chair originally had rattan braiding, adopted for English chairs from Indian furniture during the British colonial period. The rattan braiding is intact under the current cloth upholstery covering the back on both sides. The current upholstery of the chair is late but apparently from the 19th century. In the Louhisaari Manor, in Askainen in South-Western Finland, where the chair is from, there is still a neo-rococo piano stool the seat of which is upholstered with a similar fabric with a slightly different floral motif.

The secondary upholstery of the armchair, however, may relate to a certain historical context, which is why it is very important to preserve it as it is. The chair does not primarily reflect history of style, other than for its carved wooden parts, but rather a wider cultural-historical phenomenon for which it might otherwise be difficult to find concrete evidence.

The upholstery is reddish-brown shag, a napped fabric similar to smooth velvet, with a pressed floral motif. The fabric is datable to the late 1830s or early 1840s because an almost equivalent fabric was used in England for the chairs in the dining room of Charlecote Park, furnished in 1838, and in Skokloster in Sweden in 1844 for the upholstery of high-backed baroque chairs quite similar to the Louhisaari armchair. For Skokloster, the fabric was acquired in red, yellow, blue and green. At that time, the fabric was new and not in any way in accordance with the style of the chair. What, then, were the grounds for selecting the fabric for a chair more than a hundred years old?

Interest for past eras, particularly the Middle Ages, started to strengthen in architecture in the 18th century, especially in England (Strawberry Hill). In the 1820s and 1830s, this interest started to develop into fashion (Fonthill Abbey). Restorations of royal castles became models for this: the Crown Princes of Bavaria and Prussia bought themselves dilapidated medieval castles (Hohenschwangau and Stolzenfels) and rebuilt them in the 1830s so that they matched the then current idea of their original, historical appearance. In France, restoration of old royal castles (Saint-Cloud, Tuileries, Fontainebleau, Compiègne, Versailles) started in the mid-1830s, after King Louis Philippe had acceded to the throne. Later, during the reign of Napoleon III, the medieval Château de Pierrefonds, greatly admired as a “romantic ruin”, was also restored. The starting point was that the entire “historicising” interior including furniture was adapted to the age of the building. The furniture was supplemented with new furniture built according to old models or created by combining parts of items of authentic furniture. The original interior was supplemented with authentic antique furniture. Antique objects were essential for aristocratic decor, and the example set by monarchs was followed particularly among the nobility. Highlighting the position and history of one’s own family was a way to emphasise the difference, on the one hand, between the high nobility and the rest of the nobility and, on the other hand, between the nobility and the ever more prosperous bourgeoisie. The nobility saw itself as an intermediary of history between the past and the present.

Charlecote Park in Warwickshire was originally built in the 1550s, representing Tudor-era architecture and the decor of the Elizabethan era. By the end of the 18th century, however, the building had been partly refurnished. In the early 1820s, the owner of the country house at the time decided to recreate the house in its Elizabethan form by removing the 18th century interior and replacing it with “neo-Elizabethan” interior. Among other things, he had the aforementioned, completely new dining room built and furnished to match the image of the Elizabethan era.

In Skokloster in the 1830s and 1840s, Count Magnus Brahe carried out similar comprehensive redecorations for nearly the entire building, renewing or supplementing existing interiors and building completely new “17th-century” interiors to match the prevailing image of the baroque of Sweden’s age of greatness. The interior was meant to describe the living environment required by the position of one of Sweden’s most significant families and to reflect the long history of the family.

Count Carl Robert Mannerheim owned Louhisaari, a nobility palace from Sweden’s age of greatness, from 1863 to 1881, and the armchair was apparently bought from him to the museum in 1881. At the same time, other baroque furniture from Louhisaari was also acquired for the collections of the National Museum, some of which was featured in Finland’s first industrial art exhibition in Helsinki in the same year of 1881.

C. R. Mannerheim is said to have wanted to furnish Louhisaari the way it might have been furnished in its “days of glory”, i.e. the 17th century. Usually, this meant baroque furniture, although in reality, the gold baroque furniture owned by Mannerheim was a few decades newer than the Louhisaari building itself. Of course, it cannot be ruled out that Louhisaari could have featured furniture from different eras, as manors in general do. In fact, it is likely. Taking into account the minor residential use of Louhisaari in the late 17th century and early 18th century, however, it is difficult to say anything about the interior, since there is no information about it. The only 17th-century piece of furniture that is certainly from Louhisaari is a table, possibly German, which is now in Askainen Church.

Although the date of the upholstery of the Louhisaari armchair is unknown, it is unlikely that the fabric was considered old-fashioned when it was used for the upholstery. Perhaps Carl Robert Mannerheim had it installed in the 1860s or 1870s, pursuing the image of “historical truthfulness” prevalent just a few decades earlier. The disparity between the dating of the chair and the upholstery causes its own restrictions for the use of the chair in exhibitions, but the significance of the whole is in this case greater than that of the individual parts.

Jouni Kuurne

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

2019

-

Stirrup-spouted vessel from Peru

Stirrup-spouted vessel from Peru

-

Trans pride bow – a carnival accessory and statement for human rights

Trans pride bow – a carnival accessory and statement for human rights

-

Retro upholstered baroque armchair

Retro upholstered baroque armchair

-

Comb pendant from the St Nikolai shipwreck

Comb pendant from the St Nikolai shipwreck

-

Wooden toy horse

Wooden toy horse

-

Ashtray

Ashtray

-

Marsh horseshoes

Marsh horseshoes

-

Student Union flag

Student Union flag

-

Stylish at work

Stylish at work

-

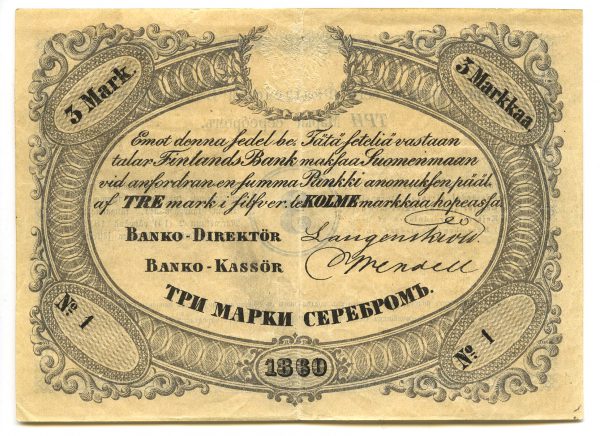

The first Finnish markka ever issued

The first Finnish markka ever issued

-

Seer's amulet

Seer's amulet

-

Photopicture from Egypt

Photopicture from Egypt

-

-

2018