Stylish at work

Artefact of the month - April 2019

The independence era collection of the National Museum of Finland was established in 2017 for the purpose of recording and documenting phenomena of the 20th and 21st century. In future, newer artefacts from the recent past, which were previously attached to the ethnological or historical collection, will be added to the independence era collection instead. One of the first donations of the collection is a dress that was made for workwear before the wars. It is a funny coincidence for the collection that the owner of the dress was born 100 years before the collection was established, meaning that she was as old as Finnish independence when the independence collection was established.

The historical collection and especially its oldest section primarily feature formal wear. This is naturally because everyday clothing was usually worn out or reused. However, formal wear saw less use, and therefore more of it survived to be preserved in a museum. The dress donation of the independence collection is an excellent addition to the museum’s materials appropriate for the ‘women and working life’ theme from between the wars.

In the 1930s, the feminine woman made a comeback to the world of fashion, displacing the boyish girl (la garçonne). She had longer and often wavy hair, which is also visible in the group photo provided. The woman emphasised her waist and wore a day dress in daytime; in the evening, she was a vamp. The first lines of homegrown Finnish design were drawn in the 1930s, and salon fashion flourished. Farmer’s son Kaarlo Forsman (b. 1907) learned how to cut fabric and sew in Lohja in the tailor’s shop owned by his sisters and by working as a modiste in the hat shop he opened in Lohja at age 21. He opened Salon Forsman in Helsinki in 1937 alongside his hat shop in Lohja. Forsman valued individuality, stylishness and quality in his work. The successful fashion salon closed in 1986.

Toini Kyttälä (married name Stenius) graduated in 1936 and continued her studies for about one year, after which she worked as an accountant and cashier at Lohjan Sähkö electric company for about a decade. The telephone was always answered in Swedish first. According to Toini, a hat was made for her at Forsman’s hat shop before she even started school. In Lohja, Kalle’s hats were said to be finer than those made by his sisters. Toini’s family frequented Kalle’s shop and even had their fur caps made there. When Toini needed an appropriate dress for work, it was easy to turn to a familiar craftsman. A telephone call to Helsinki was all that was needed to place the order because Toini wore a very standard size.

The unlined dress with a waist seam is sewn from a thin silky fabric with small pink shapes on a dark blue-violet background. The front pockets are delightfully trimmed with pink crepe. The pattern was probably designed by Forsman, and the material was the shop’s patterned silk or possibly some regenerated fibre. The front pieces continue jacket-like down to the hip, and the slit is closed with fabric-covered buttons. The shoulder line was emphasised by gathering the short sleeves at the shoulder seam. The figure-hugging shape was achieved by taking in both the bodice and waist. For looseness, the back has four deep pleats that are attached to the shoulder yoke at the top and the waist seam at the bottom. In the skirt section, the pleats are sewn at the top and left loose at the bottom for easier movement. The belt loops at either side of the waist indicate that the dress used to include a belt. The collar in the group photo was probably made of the same fabric as the pocket trim.

Toini’s dress represents modest everyday fashion in Forsman’s works – after all, in the late 1930s, his salon was only just starting out. Nevertheless, its spirit and material are very close to a summer suit made by Atelier Manon in Helsinki around the same time, which was donated to the collections by Professor Riitta Pylkkänen (PhD), who was a costume historian. It is made of black-and-white double-weave French silk fabric patterned with twigs with berries. The subtle suit includes a short-sleeve belted jacket and skirt. The light side of the fabric was used in the collar to brighten up the otherwise dark ensemble.

The zip is often mentioned as a 1930s invention, but it was patented in the Unites States at the beginning of the 1900s. However, zips were still rare in the side slits of skirts and dresses, although they were used in other garments, such as purses, pockets and even trousers. Neither of the aforementioned dresses has a zip.

In the 1930s, dress patterns had a lot of variety and decorative details. Romantic playfulness was achieved through flowery patterns, cuts, different types of belts and buttons as well as carefully considered colour combinations. Shoulders were emphasised with pleated puff sleeves or shoulder flounces and, above all, shoulder pads. In all its modesty, Toini’s work dress also reflects these trends of the time. However, all good things must come to an end, and the war brought sobriety to fashion. The ‘well-dressed career woman’ had actually already been analysed in fashion magazines in the decade before and, before the war, many shops and banks had uniform work dresses made for their personnel.

Outi Flander

Satu Lahti’s master’s thesis on the works of Salon Kaarlo Forsman (Craft Science 2010, Helsinki University), open here.

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

2019

-

Stirrup-spouted vessel from Peru

Stirrup-spouted vessel from Peru

-

Trans pride bow – a carnival accessory and statement for human rights

Trans pride bow – a carnival accessory and statement for human rights

-

Retro upholstered baroque armchair

Retro upholstered baroque armchair

-

Comb pendant from the St Nikolai shipwreck

Comb pendant from the St Nikolai shipwreck

-

Wooden toy horse

Wooden toy horse

-

Ashtray

Ashtray

-

Marsh horseshoes

Marsh horseshoes

-

Student Union flag

Student Union flag

-

Stylish at work

Stylish at work

-

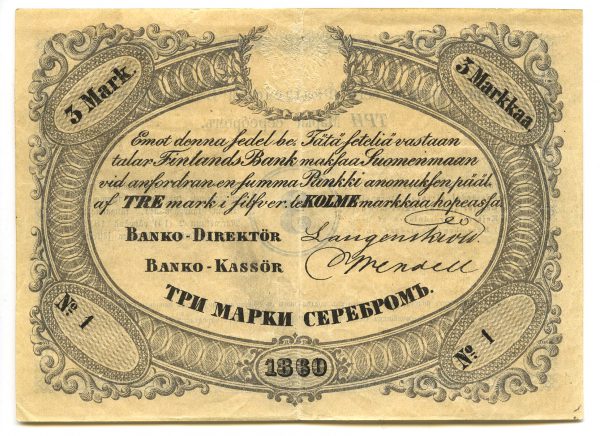

The first Finnish markka ever issued

The first Finnish markka ever issued

-

Seer's amulet

Seer's amulet

-

Photopicture from Egypt

Photopicture from Egypt

-

-

2018