Two mermaids

Artefact of the month - February 2020

"A human fish with the back half of fish and the front half of a horrid humanoid monster. The creature’s webbed and clawed hands stretched out as if to swim in crawl, its face frozen in a silent scream of terror."

Astonishing tales, unbelievable artefacts – our collections hold many kinds of treasures. An artefact does not need to be all gold and glitter to impress. Every item tells a story that can open a panoramic view into the past. The manufacture and use of an object, along with the meanings linked to the various phases of its life, rise to the fore through contextualisation – examination of its path through time and cultural environments. Why was it made, who used it and what was thought of it? What broader phenomena is it connected to?

Two mermaids have found their way into the National Museum of Finland’s ethnographic collection. They are brought to the surface from time to time by those looking for something bizarre in our collections. I first came across them in 1996 while looking for items to display in the exhibition of curiosities that was being planned. This sparked a journey of discovery into the mermaids’ past. I began to find information from the most peculiar of sources, ranging from the "Fiji Mermaid" featured in an episode of X-Files to the taxonomies of the Finnish Museum of Natural History. You could say that, quite appropriately, the mermaids led to a literal flow state in my investigation efforts.

To get started, I naturally had to trawl the depths of the museum itself.

The first mermaid (VK765), which has been shaped into a floating posture, came to our ethnographic collection in 1867, having initially sailed from the "Southern seas" onboard Captain O. W. Lindholm’s ship to the Zoological museum of the Imperial Alexander University, from which it was brought to us as a collection transfer. The item was thought to be a fetish, a kind of magical object, which may be why the specification "artificial" was included in the item catalogue, as if to provide some kind of assurance. I decided to call the mermaid Vetehinen, after the shapeshifting water spirit in Finnish mythology.

Its crawl-swimming sister (VK5054:71), dubbed Vellamo after the early Finnish goddess of water, was moved into the National Museum’s "exotic collection" from the Helsinki City Museum in 1925, but there is no record of its path to Finland.

Who made these grotesque mermaids and why? Captain Lindholm (1832–1914) sailed on cargo ships headed to Alaska and on whaling ships cruising the North Atlantic, also visiting the Palau islands and apparently Japan, among other destinations. I was also steered towards the same course by P. F. von Siebold’s book depicting life in 1820s Japan. It includes an anecdote of a fisherman who made a mermaid from monkey and fish parts, claiming he had caught it live in his net. Before its demise, the creature had supposedly had time to utter a religious prophesy – go figure!

If he even existed, this fisherman was by no means the only mermaid crafter around. In Japan, the traditional mermaid figure is called ningyo, literally 'human-fish'. If caught in a fishing net, a ningyo was believed to portend storm or calamity and must be released back into the sea. At the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, ningyo figures were made for display at misemono carnevals, alongside other extraordinary crafts items. It is likely that the first mermaids were brought onboard European ships at the Dutch trading post in Nagasaki Bay during the Edo period when the rest of Japan remained closed off from the outside world.

In addition to Japan, similar aquatic creatures probably began to be fabricated also in the coastal villages of Indonesia, Melanesia and Polynesia for bartering to travellers and seafarers. Materials such as animal parts, papier-maché, cloth and iron wire were used in the fabrication process. Even Vetehinen and Vellamo have the tail of a perciform fish, but Vetehinen has the jaws of a lizard with teeth and claws made of porcupine quills, while Vellamo has the needle-toothed jaws of a small fish and the claws of a fowl on its fingers. Monkey parts are nowhere to be found.

Various water spirits and deities are always found wherever there is water, and related beliefs are sure to have fuelled the continued use of these faux mermaids. In the 19th century, they were presented in Europe and the United States as real mermaids. The cabinets of curiosities that came about in the 16th century and can be regarded as early precedents of museums contained an assortment of wonders, such as body parts of mermaids as well as narwhal tusks, which were thought to be unicorn horns. The American Museum which operated in New York in the mid-19th century followed along the same lines, with the exception that the foremost goal of its owner P. T. Barnum was to make as much money as possible. In 1842, the much-touted main attraction of his business was, lo and behold, a mermaid. The "Fiji (Feejee) Mermaid" was of course marketed as a genuine, albeit dried up, sea creature, and it is the very one that appeared in an X-Files episode scrawled on a restaurant menu.

The Fiji mermaid was quickly revealed to be a fake, or rather a genuine man-made artefact. However, this relatively innocent scam eventually took a more serious turn as the Fiji mermaid swam its way into public consciousness before the American Civil War in the context of racial segregation. The mermaid was drawn into the ongoing debate about the constancy of species and the existence of a divine plan. Defenders of slavery claimed that its existence proved that species had been created at different times to be permanently disparate, which meant that there was no unity to be found within the human race either. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was not published until 17 years after the debut of the Fiji mermaid.

The current globally prevalent conception of a mermaid is a mix of characteristics from many cultural traditions from Africa, Asia and Europe. Its history can be traced far back all the way to the Greek sirens, the apsara nymphs in Indian mythology (the Sanskrit word refers to something that moves in water) and the later Mami Wata, which is an amalgamation of features from many African traditions. The historical links behind these concrete representations of mermaids, including their manufacture and use to visualise semi-human creatures of the sea, inexplicably link them to our conceptions water spirits as a broader category. These fake mermaids are one corner of the vast landscape of traditions relating to water spirits and deities – attempts to substantiate the mythologies and beliefs created by human cultures, and often earn some money in doing so.

Vetehinen and Vellamo are now on display in the Maritime Museum of Finland to contribute to the North Star, Southern Cross exhibition. Their aquatic sisters can be found in the collections of many museums in Europe and the United States, such as the Horniman Museum in London and the Peabody Museum of Harvard University in the United States. Some are also held in private collections, and recently instructions on how to make a mermaid of your own have been published online. In short, the monstrous mermaid continues to fascinate us in many ways: “A fabricated monster is only one step removed from an imagined one.” (Dance 1976, 8.)

Pilvi Vainonen

Sources and reading:

Barnum P. T. 1888. Life of P. T. Barnum Written by Himself. The Courier Coumpany Printers, Buffalo.

Benwell Gwen and Arthur Waugh 1961. Sea Enchantress. The Tale of the Mermaid and her Kin. Hutchinson, London.

Borges Jorge Luis 1987 (1967). The Book of Imaginary Beings. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth.

Coleman Lauren 2009. NINGYO. The Story of Japanese Mermaids, Part 1. Cryptomundo. https://cryptomundo.com/crypto...

Dance Peter 1976. Animal Fakes & Frauds. Sampson Low.

Dance Peter 1978. The Art of Natural History. The Overlook Press, Woodstock.

FAKE? The Art of Deception 1990. Eds. Mark Jones, Paul Craddock and Nicolas Barker. British Museum Publications.

Goodman Ailene S. 1983. The Extraordinary Being: Death and the Mermaid in Baroque Literature. Journal of Popular Culture Vol. 17 No. 3 Winter 1983, 32-48.

Harris Neal 1973. Humbug. The Art of P. T. Barnum. Little, Brown and Co.

Houlberg Marilyn 1996. Sirens and Snakes. Water Spirits in the Arts of Haitian Vodou. African Arts, Spring 1996, 30–35.

Leikola Anto 1992. Seireenien taru: syöjätärlinnuista pikku merenneidoiksi. Portti, 4/1992, 78–85.

Mami Wata. Arts for Water Spirits in Africa and Its Diasporas 2008. Ed. Henry John Drewal. Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles.

Ningyo: Vintage Japanese Mermaids 2014. Lazer Horse. http://www.lazerhorse.org/2014...

The Feejee Mermaid. The story of history's most famous mermaid, that fascinated audiences in the nineteenth century. Museum of Hoaxes. http://hoaxes.org/archive/perm...

Vainonen Pilvi 1996. Mistä tulet, merenneito? HS, Kuukausiliite, heinäkuu 1996, 34–36.

Vainonen Pilvi 1997. An Event of Curiosity: When a Mermaid Fake Crawled on a TV-Screen. Nordisk Museologi 1997, 1, 107–116. https://journals.uio.no/index....

Vainonen Pilvi 2010. Helinä Rautavaara ja merenneidot. Kuriositeettikabi.net 1/2010, Museion, Turun yliopisto ja Åbo Akademi. http://kuriositeettikabi.net/n...

Werner M. R. 1923. Barnum. Harcourt, Brace and Co.

Viscardi Paolo, Anita Hollinshead, Ross Macfarlane & James Moffatt 2014. Mermaids Uncovered. Journal of Museum Ethnography, no. 27 (2014), 98-116. https://paolov.files.wordpress...

Viscardi Paolo 2014. Mysterious mermaid stripped naked. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sc...

von Siebold P. F. 1981 (1841). Manners and Customs of the Japanese in the Nineteenth Century. Charles E. Tuttle Co.

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

-

Chilkat blanket

Chilkat blanket

-

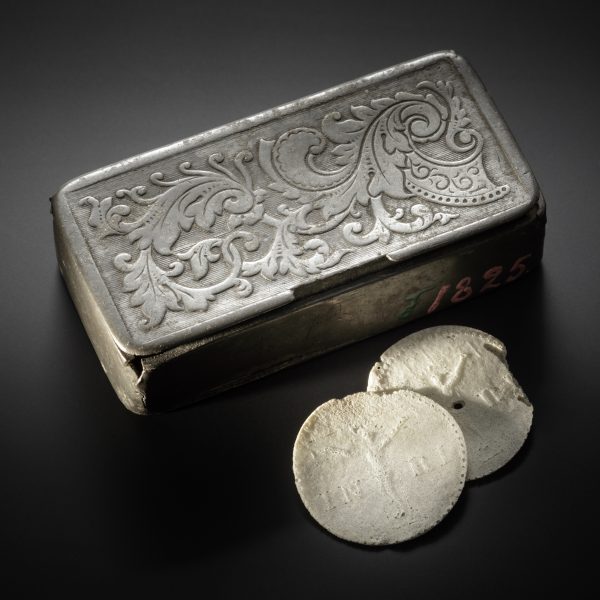

A box of sacramental bread

A box of sacramental bread

-

Tar steamer model

Tar steamer model

-

A holy family from the court of Prague?

A holy family from the court of Prague?

-

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

-

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

-

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

-

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

-

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

-

Two mermaids

Two mermaids

-

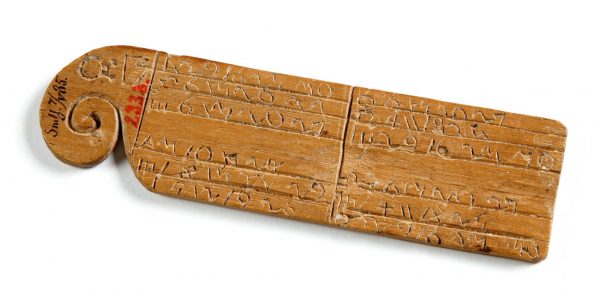

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

-

-

2019

-

2018