Mosquito hood from East Karelia

Artefact of the month - July 2020

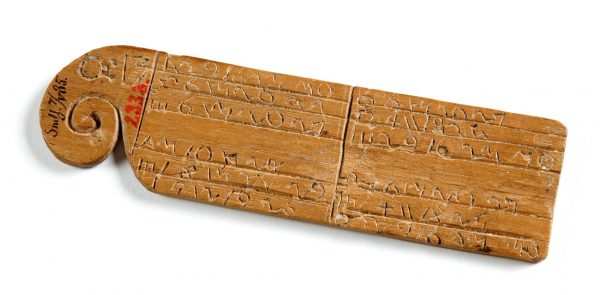

Nematocera, and their subspecies the mosquito, are unwanted companions during summer evenings and in the shade this time of year. Trying to protect yourself from these bloodsuckers is a generational experience, but only a few items related to this plight have been gathered to the National Museum of Finland. These include the rankinen, or mosquito cover, in the Sámi collections, a fan made of bird feathers found in Siberia and a small horn for keeping pitch oil for oiling the hands and face. Headwear consisting of mosquito hoods made from linen or cotton also belong to the collection.

A hooded piece of headwear belonging to a man’s or woman’s outfit was already used in the Middle Ages both in the East and the West. A piece of clothing used to cover the shoulders, neck, throat and ears was very practical while travelling in cold weather. The flaps could be lifted and attached to the top part, if necessary. In the East, the dead were also dressed in hood-like headwear. The kukkeli (tšubruna in northern Olonets), which was part of burial clothing for both men and women, was a long body-length dress open at the front and closed with ribbon below the chin.

The collection of the National Museum of Finland includes four mosquito hoods from East Karelia. There, hunters used to wear them as protection from tšakkas, mosquitos, but the headwear was also used previously in slash-and-burn areas to protect the wearer from the heat. Ilmari Manninen, a young man with a master’s degree, acquired two mosquito hoods for the collection of the National Museum of Finland during his trip to Olonets Karelia in the summer of 1917.

He went on his collection trip during a historical time between two revolutions. Tsar Nicholas II of Russia had been overthrown in March (in February in Russia) and the October Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks took power, was a few months in the future. In the Grand Duchy of Finland, this was followed by the Finnish independence from Russia in December 1917 and the Finnish Civil War in early spring 1918. The uncertain times affected Manninen’s trip to the extent that some of the items he had collected were left behind the border, even though he had already paid for their shipping. Ultimately, the collection of 94 items arrived at the National Museum of Finland in 1919.

Ilmari Manninen, who had toured the villages of Olonets Karelia, always looked to the past, recording old customs and disappearing folk culture, which he was looking for especially in the remote areas of northern Olonets. He also observed the changes brought on by roads, shopping trips to bigger towns, and the segregation of trades. Hunting, for example, was increasingly only performed by professional hunters. The mosquito hoods, which were made completely by hand, were made with cotton, which proved that store-bought fabric was becoming more common.

The mosquito hood, also called a kukkeli, itikkahattu or tšakkalakki, was a striking garment from the point of view of an outsider. The attention paid to the headwear by collectors is testament to that. In addition to the hoods brought back by Ilmari Manninen, similar pieces have been gathered to the National Museum of Finland as a result of trips by photographer I. K. Inha and architects Yrjö Blomstedt and Victor Joachim Sucksdorff in 1894.

The intrigue of the headwear is also evident in artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s choice of including the mosquito hood as a symbol for the East Karelia coat of arms in addition to a bear holding a billhook, broken silver chains and wolf tooth belts. Gallen-Kallela drafted a flag and coat of arms for East Karelia in the spring of 1920, when the attacks started by Finnish Finno-Ugric activists in East Karelia in 1918 were coming to an end.

The armed operations of the forces in Belomorsk and Olonets Karelia had not yielded the desired results. Beyond the border on the Russian side, the Finns met reserved and confused Karelians, who did not agree with the objective of annexing East Karelia to Finland as eagerly as the Finns had expected. The direction of Finnish foreign policy took a more peaceful turn with the election of President K. J. Ståhlberg in 1919. The Treaty of Tartu between Finland and Soviet Russia was signed on 14 October 1920. The peace terms were a disappointment for the supporters of the Finno-Ugric activists’ ideology.

Some of the symbols of East Karelia designed by Gallen-Kallela, with the mosquito hood included, have been embroidered onto a small tablecloth donated to the National Museum of Finland collection from the estate of Anni and Wasili Keynäs. The family ended up living on the Finnish side of the border much like the more than 33,000 Karelian and Ingrian refugees who moved here from the east side of the border in the turbulent years around 1920.

The items are not currently on display.

Anna-Mari Immonen

Sources:

Laine Antti 1998. Venäjän Karjala 1900-luvulla. In: Karjala, historia, kansa ja kulttuuri, eds. Pekka Nevalainen & Hannes Sihvo. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Helsinki.

Laurla Kari K. 1997. Itä-Karjalan tunnuksia. Collegium Heraldicum Fennicum ry/Airut. Helsinki.

Manninen Ilmari 1919. Kansatieteellisiä kertomuksia Pohjois-Aunuksesta. Porvoo.

Manninen Ilmari 1932. Karjalaisten puvustosta. In: Karjalan kirja, ed. Iivo Härkönen. Porvoo.

Roselius Aapo & Silvennoinen Oula 2019. Villi itä. Suomen heimosodat ja Itä-Euroopan murros 1918–1921. Helsinki.

Sihvo Pirkko 2005. Miesten päähineet. In: Rahwaan puku. Näkökulmia Suomen kansallismuseon kansanpukukokoelmaan, eds. Ildikó Lehtinen & Pirkko Sihvo. Museovirasto, Helsinki.

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

-

Chilkat blanket

Chilkat blanket

-

A box of sacramental bread

A box of sacramental bread

-

Tar steamer model

Tar steamer model

-

A holy family from the court of Prague?

A holy family from the court of Prague?

-

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

-

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

-

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

-

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

-

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

-

Two mermaids

Two mermaids

-

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

-

-

2019

-

2018