Oak night-box (nattlåda)

Artefact of the month - April 2020

Sweden’s age of greatness (from King Gustavus Adolphus to the death of Charles XII) was the age of Baroque and dominance of the nobility. Furniture models arrived in Finland via Stockholm with French influences or as more modest English-Dutch versions. Finnish cabinetmakers crafted chairs and tables mainly according to the English-Dutch style, while cabinets and chests were made according to northern German and Dutch models. Finnish furniture was crafted from oak or oak veneer, but softer wood was selected particularly for furniture with decorative carvings.

Chests were the most typical pieces of furniture used for storage in the 16th and 17th centuries. It is the most common type of furniture in estate inventories of both the nobility and the bourgeoisie in Sweden. Many chests were actual luxury items. In Finland, chests in the Renaissance and Baroque periods were mainly imported goods, and even local master craftsmen had often come from abroad to practise their trade. Such splendid oaken furniture, decorated with incisions, was acquired by the nobility for their manors, particularly during the short reign of Duke John in Turku in the mid-16th century. Painted decorations appeared on the interior of the lids and front sides in the 17th century: the names of the bride and groom, the crests and the year amid acanthus and laurel branches.

A particular type of chest is the night-box (nattlåda in Swedish), which was a utility item of the upper class. They were particularly common from the late 17th century to the mid-18th century. The term nattlåda was used in estate inventory deeds and inventories, and those who had this piece of furniture in their homes in Finland at the time likely referred to it by this Swedish name. The finest linen and valuables, such as watches, jewellery and toiletries, were kept in the night-box overnight. The box often served as a piece of luggage and household furniture. Sometimes it had a skilfully carved or turned base. These boxes became widely used beyond the royal court during the 17th century. The Journeymen’s Guild in Turku considered including this artefact in their masterwork in 1712.

Several Swedish inventory notes about these chests remain from Sweden’s age of greatness: they were often made of wood such as oak, ebony – a favourite of the era – or black-painted pear tree, but olive and birch were also used. Some were covered with valuable fabric or decorated with silver. Estate inventory research on furniture in Gothenburg revealed that nearly all night-boxes recorded in the city in 1668–1788 were equipped with a lock, key and fittings.

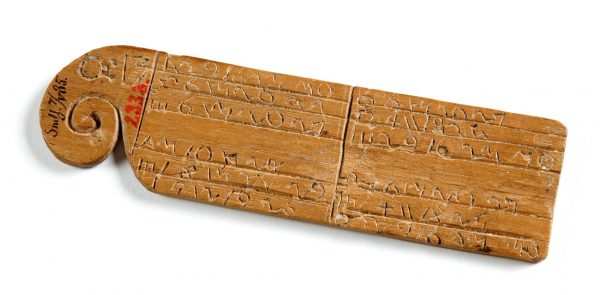

A night-box is the general name for a relatively large, quite shallow, square-shaped box with a flat lid. One of its varieties is a similar, rectangular small chest with a dome-shaped lid. A night-box always has a lock, and some have handholds on both ends or one handhold on the lid. It has a sturdy structure reinforced by external fittings. The finest boxes were decorated in various ways: tortoiseshell, ebony and ivory were used for inlays and white taffeta was used for lining. Lacquerworks were also popular. However, the most common material was oak along with tin-coated iron fittings. Decorative carvings, bas-reliefs or paintings were applied to the boxes to add some variety. In the 18th century, all four social classes already had such night-boxes in their possession.

Gradually, the very useful and popular artefact went out of fashion and was replaced by other pieces of furniture used for storage, such as drawers. However, it remained relevant in peasant culture all the way to the early 19th century. In Sweden, the original name and function of the night-box fell into obscurity in the latter half of the century. August Strindberg, who was well read in his country’s cultural history, placed a countess’s night-box quite correctly in a Baroque milieu in his book Svenska öden och äfventyr (1882). Nevertheless, Verner von Heidenstam was not wrong in his book Karolinerna when he depicted such a box with a tobacco can in a man’s room to represent the spirit of the times. Still, the night-box was a piece of furniture mainly used by women in royal and aristocratic households. As the practice spread to wider social circles, its use became a rule rather than exception.

One of the night-boxes in the National Museum of Finland’s collection is very interesting, not least because of the painted decorations on the interior of the lid. The rectangular, shallow box (65 x 52 x 21 cm) is made of oak and its bottom is pine. There used to be a shelf and, possibly, a removable drawer for small items on the left end of the box. The flat incised decorations on the exterior sides follow distinct Renaissance contours, which were typical in countries such as Germany. Cloverleaf rosettes decorate the corners and centre of the flat hinged lid. The ends have iron supports, the corners have fittings with scalloped edges, the keyhole escutcheon is broken and the key is missing. Background information on the box is incomplete: it was purchased by the museum from G. Karlsson in Kirkkonummi in 1910. It can be dated to the latter half of the 17th century. A closer look provides various hints regarding its date of origin, which may not be obvious at first glance.

The interior of the lid has a painting of four bourgeois women: Frau Magdalena and her daughters. The ladies have been depicted in order of height in the manner of votive tablets, as if they were moving towards a cross in the middle. The cross is missing just like the male members of the family standing on the other side of the cross. The outfits of bourgeois women sometimes combined several fashion characteristics from different eras. In the image, all women are wearing a fashionable dress from around 1670, based on the short sleeves. In contrast, their hairstyles with bangs represent fashion from the mid-17th century. Each woman is wearing a red and white ribbon in their hair, which renders their dark tresses visible particularly with the daughters. A belt-like collar frames the boat-shaped neckline. The cross lacing of the corseted bodice and narrow white aprons indicate that the lady and her daughters belong to the Estate of the Burgesses. In her left hand, the mother is holding a half-open folding fan, which in this case is highly fashionable, while her daughters hold a flower. All of them have short, fashionable pearl necklaces, and the bodices are adorned by a rosette or piece of jewellery. The background consists of parklike greenery dotted by flowers; trees that slightly resemble pines can be made out at both iron hinges. There are particular sections placed symmetrically at the height of the women’s faces. These spaces are marked off by black lines that meet in a rectangular fashion, and one corner has a vertical red and white rectangle. There is a bunch of trees in this section on the right of the right hinge. Instead of trees, there are red fields marked in black on the right of the left hinge. The paint is so faded that the section is difficult to make out. There is a trumpet floating in the sky above. There is a black letter, possibly F or JF, in the air in front of the trumpet. The text below this section possibly reads “E. Frau Magdalena P”, which would mean “honourable lady Magdalena P”.

When one looks at the painting for a long time, many thoughts and questions arise that may never be answered. First of all, it is one of the earliest remaining examples of fans being used in Finland. Fans are quite often featured in Swedish portraits of the time, but there are only a few such early examples in Finland. The Ristiina Church, however, has a portrait of Countess Kristina Katarina Stenbock (from around 1640). The countess is clearly holding a two-toned fan made of ostrich plumes in her left hand. The collections of the Turku Museum Centre include a portrait of Magdalena Wernle, a wealthy merchant’s wife based in Turku. The fashionable lady is holding a latticed folding fan with dark patterns. Introduced in Southern Europe from the East, fans were part of the fashionable attire of upper-class women as early as the 17th century. In the wake of the French wave of fashion, fans became more common in the late 17th century. Their use peaked in the 18th century, when manufacture of folding fans became an important part of the fashion industry in France. It is interesting that this luxury item, which was rare in Finland at the time, was portrayed in such an ordinary utility item as the night-box. The depicted attires of the burgher women clearly demonstrate that fashionable dresses were not exclusively worn by the nobility in Finland in the late 17th century. The painter was likely familiar with fashion drawings of the time period, which frequently feature fans together with a dark mask protecting the subject’s face. The fan is held correctly in the image, but the painter may not have been completely familiar with what they were depicting. A similar example can be seen in a painting on the interior of the lid of a secretaire in the collection of the Rauma Museum. In the painting, a couple is depicted walking on a beach with their dog, wearing a manteau and a coat outfit from the 1680s. The woman is holding a fan and the man is wearing a hat with a brim. The Renaissance-style oak chest was made in 1673 and was acquired by the National Museum from the Laukko Manor in Vesilahti. The painting on the interior of the chest lid depicts a noble couple wearing the black court attire of the era: the man wears a coat outfit and the woman’s dress has short sleeves, revealing baggy shirt sleeves. The interior of the chest is lined with fashionable French copperplates (Bonnart, Paris around 1680, Mercure Galant magazine).

The paints on the box are so badly faded in places that the item’s background leaves much room for speculation. The mushroom-like trees bring to mind pines resembling umbrellas from the imagery of ancient Rome, and the rectangular shapes make one think about fence structures in old garden paintings. What does the trumpet in the sky mean, and the red scenic rectangular shapes? Do the garden and flowers in the background refer to another, more perfect world? Did the painter intend to symbolise holy harmony, a beautiful garden? In 17th-century painting, Fame is depicted as a woman with a trumpet and, occasionally, angel wings. Could it be that the smeared paint at the end of the instrument hides someone who is blowing the trumpet in praise of Frau Magdalena? All in all, the womenfolk have been depicted in such an impressive way that one is tempted to come up with a companion piece for the box: a similar box for lady Magdalena’s husband – featuring the coat-attired men of the family on the lid.

The night-box 5626 is currently not on display.

Outi Flander

Literature:

Arkku. Arkkuja Tampereen kaupungin museoiden kokoelmista. Tampereen kaupungin museolautakunnan julkaisuja 6, 1974. Text by Leena Willberg. Tampere.

Knutsson Johan 1989. Barockmöbler på Skokloster. Stockholm.

Kulturen 1944, 1967, 1981.

Pylkkänen Riitta 1970. Barokin pukumuoti Suomessa 1620-1720. Helsinki.

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

-

Chilkat blanket

Chilkat blanket

-

A box of sacramental bread

A box of sacramental bread

-

Tar steamer model

Tar steamer model

-

A holy family from the court of Prague?

A holy family from the court of Prague?

-

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

-

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

-

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

-

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

-

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

-

Two mermaids

Two mermaids

-

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

-

-

2019

-

2018